Ursula K. Le Guin: The Crossover Artist

Ursula K. Le Guin is one of those rare figures in the world of science fiction: the successful crossover artist. Her most famous novels profile the political, religious and cultural dilemmas of her interplanetary League of Worlds. Her work appeals to readers who would not otherwise describe themselves as admirers of the form; readers who generally understand the activities of science and fiction as belonging to separate hemispheres of the brain.

In fact, Le Guin views the great divide between speculative and realistic literature as a false and arbitrary construction. Indeed, she sees the two genres as simply employing different means to achieve the same objective: While realistic fiction often uses the past to explain the present, science fiction uses the future to do the same thing.

Le Guin explains: "What I do in my fiction is talk about the so- called future. But it's really a way of looking at the right-now. To paraphrase the Montreal writer Darko Suvin, 'Science fiction is like taking a mirror and looking at the back of your head.' It is just looking at the present from a different angle."

It does not surprise Le Guin that a number of high-profile women writers including Doris Lessing (Canopus in Argos) and Margaret Atwood (The Handmaid's Tale, The Blind Assassin) are responding to the limits of realism by turning to science fiction. "Science fiction is marginalized," she says, "and so are women. And we know where we belong. Science fiction also offers alternatives. It suggests other ways of being. This is perhaps more important to women than it is to men," she adds, a trifle archly.

Nevertheless, practitioners of science fiction tend to see themselves as the Rodney Dangerfields of the literary world -- they don't get no respect. Yet Le Guin can count herself among the contemporary sci-fi authors who represent an exception to the rule. Her first novels in the interplanetary Hainish series (Rocannon's World, Planet of Exile and City of Illusions) appeared in 1966 and 1967. But it was The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) that marked Le Guin's official arrival. The novel anticipated the debate over gender that would fuel the women's movement and earned Le Guin a Nebula Award and a Hugo.

Over the next 40 years, her work would garner her armloads of sci-fi prizes. In 1973 she received a National Book Award for Children for The Farthest Shore, the third book in her Earthsea trilogy. The fantasy series is a clear precursor to Harry Potter. Le Guin has written more than a dozen novels, published several volumes of poetry, edited numerous anthologies and essays and in 1998 published a collection of her own thoughts about writing, Steering the Craft.

Critic Harold Bloom, one-time gatekeeper of the Western canon, includes Le Guin on his list of major 20th-century authors, although, like many critics, Bloom sees her elegant prose, sensitively drawn characters and superbly articulated themes as elevating her above the realm of science fiction. But don't do Le Guin any favours. She is nothing if not a loyal member of the science fiction community and is not about to be bullied into the mainstream.

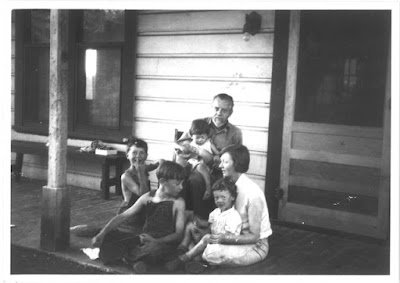

Ursula K. Le Guin on the knees of Alfred Louis Kroeber; sitting Theodora Kroeber-Quinn with Karl, Cliffton and Theodore

I reach Le Guin in Portland, Ore., at the Victorian home she shares with her husband of nearly 50 years. We are scheduled to discuss her latest book, The Telling. But when she comes to the phone she sounds a little frazzled. "I am just putting on the pasta," she says with an apologetic laugh. "Could you give me another half-hour?" It's 10:30 p.m. in Toronto when the interview gets underway, though in Portland it's early evening. Our words waft across lines of longitude as easily as her characters travel in time.

Just about the first thing that strikes one about Le Guin is that she is a woman completely at home with her own unconventional opinions. It's a trait she credits to her parents.

Ursula Le Guin was born Ursula Kroeber in Berkeley, Calif., in 1929. Her father, Alfred, founded the prestigious anthropology department at the University of California at Berkeley. Her mother, Theodora, was a writer with a master's degree in psychology. As often as possible the Kroeber's encouraged their daughter to lean on her own understanding, even when it came to issues as significant as religion.

"I wasn't taught anything about religion," Le Guin says. "The U.S. is a deeply religious country. Very Protestant. Very Christian. But I was brought up totally outside that. I came to the subject totally virginal. Religion has always fascinated me as things fascinate the outsider. The thing that worried me was that in the U.S. you are told over and over that religion and morality is the same thing. I know from my own experience that that's not true."

Le Guin's concerns about religion are manifested in The Telling, in which Sutty the young, gay heroine, relives horrific memories of growing up on Earth under a fundamentalist regime. Sutty travels forward in time to the planet Aka in order to study its language, history and religion. But when she arrives, she finds that Aka's rabidly capitalist government -- The Corporation -- has outlawed the teachings of the past. The Telling, like all of Le Guin's work, explores her longstanding interest in Taoism, which is sometimes described as the philosophy of "live and let live."

"In The Telling I am attempting to show that if you go too far in one direction you begin to swing back in the other direction. This is the Tao principle of yin-yang, yin being the feminine element and yang being the masculine. I'm trying to describe a culture that has been very yin, and in a generation or two has gone yang. But you can't go that far yang or you start swinging back."

Le Guin's fascination with Taoism began in her teens when she noticed her father reading the Tao Te Ching, which contained Taoism's sacred tenets. "It was this weird little book," she recalls. "I just loved the text ... and I loved it the rest of my life."

She's not exaggerating. From the late 1950s to the late 1990s, while raising three children (two girls and a boy), and churning out fictions and fantasies, essays and poems, Le Guin worked on a new version of the "weird little book." To modern minds, it seems a painstaking, anachronistic task. One pictures Le Guin, sequestered in close, dank quarters, perusing frail, mouldy tomes, like the eccentric scholar Casaubon in George Eliot's Middlemarch.

Le Guin laughs heartily at the image: "It wasn't that way at all," she says. "Lao-tzu [c. 575 - c. 485 BC], the author of Tao Te Ching, is really kind of lighthearted. Deep and sweet. And besides, I took it slow. I never worked on it unless I wanted to. Ever."

According to Le Guin, she never does anything unless she really wants to, but adds that such freedom has only been made possible by the unswerving support of her husband, historian Charles Le Guin. "Every successful woman writer I know has had strong in-house support."

If Taoism comprises one important aspect of Le Guin's personal philosophy, her belief in the sacredness of the word comprises another. Storytelling was a habit with the Kroeber family, especially during summer months, which they spent on their ranch in California's Napa Valley. After nightfall, Ursula would join her parents and brothers outdoors around a blazing fire, and her father would regale them with his favourite Native American legends. Le Guin works these memories into her novel. In The Telling, the mountain folk come together secretly during winter evenings so they can listen to the Maz (elders) recount the stories the government has banned.

Le Guin in the 1970s (photo: University of Oregon Libraries)

Says Le Guin, "There is a relationship between what the Maz do and what novelists do, and what novelists do and what shaman do. When its cold and nasty, the Native Americans gather round and tell certain stories about winter.

"One of the functions of storytelling is to hold people together," says Le Guin. "To say 'This is what we come from. This is who we are.' "

If there is one particular reason why Le Guin's science fiction attracts so wide a readership, it is the fact that her stories emphasize the social sciences -- psychology, sociology and anthropology -- over the "hard" sciences, such as engineering and technology. Her science focuses on human interaction and emotion. She investigates the ramifications of our treatment of one another. She is convinced the way we mismanage our collective stories -- our histories and cultures -- will have serious repercussions.

"Science fiction is about continuity," she explains. "A lot of writers are perfectly happy not to have continuity. They don't think of the past and they don't think of the future. They just lump along in the present. That worries me."

An earlier version of this piece appeared in the National Post.