Revisiting Priscila Uppal's Closet

Every once and a while some Canadian literary type will howl out into the universe, "How I miss Priscila Uppal!" Then I begin to remember too. Only, I never really forget: Uppal is a hovering presence, a creative energy that continues to burn. She was a friend, who belonged to this rather remarkable group of artistic women I used to meet up with. She was the youngest of us, and the most accomplished, already a tenured professor at some ridiculously youthful age, a star of poetry (shortlisted for a Griffin), fiction, memoir (shortlisted for a Hilary Weston Writers Trust Prize), essays, photography, drama. She wrote pop-up poems for the Winter Olympics, was The Canadian Athletes' Writer in Residence and regularly ran marathons herself. She was playful, yet glamorous -and a world traveller. She took her understanding of the world from Cervantes, specifically, Don Quixote. She was a great giver of gifts and of her time - passionately devoted to her family, to her friends and especially to her students, who recognized in her a teacher, a mentor, an Auntie and a boon companion. She grew up under the most challenging circumstances- her father caught meningitis after falling out of a canoe into the Caribbean Sea. In a matter of hours he became quadriplegic. Uppal was two years old. Her mother - unable to endure the emotional strain, eventually fled the situation, abandoning Uppal and her brother, still children, to cope with their physically dependent father (this is the painful subject of her memoir Projection).

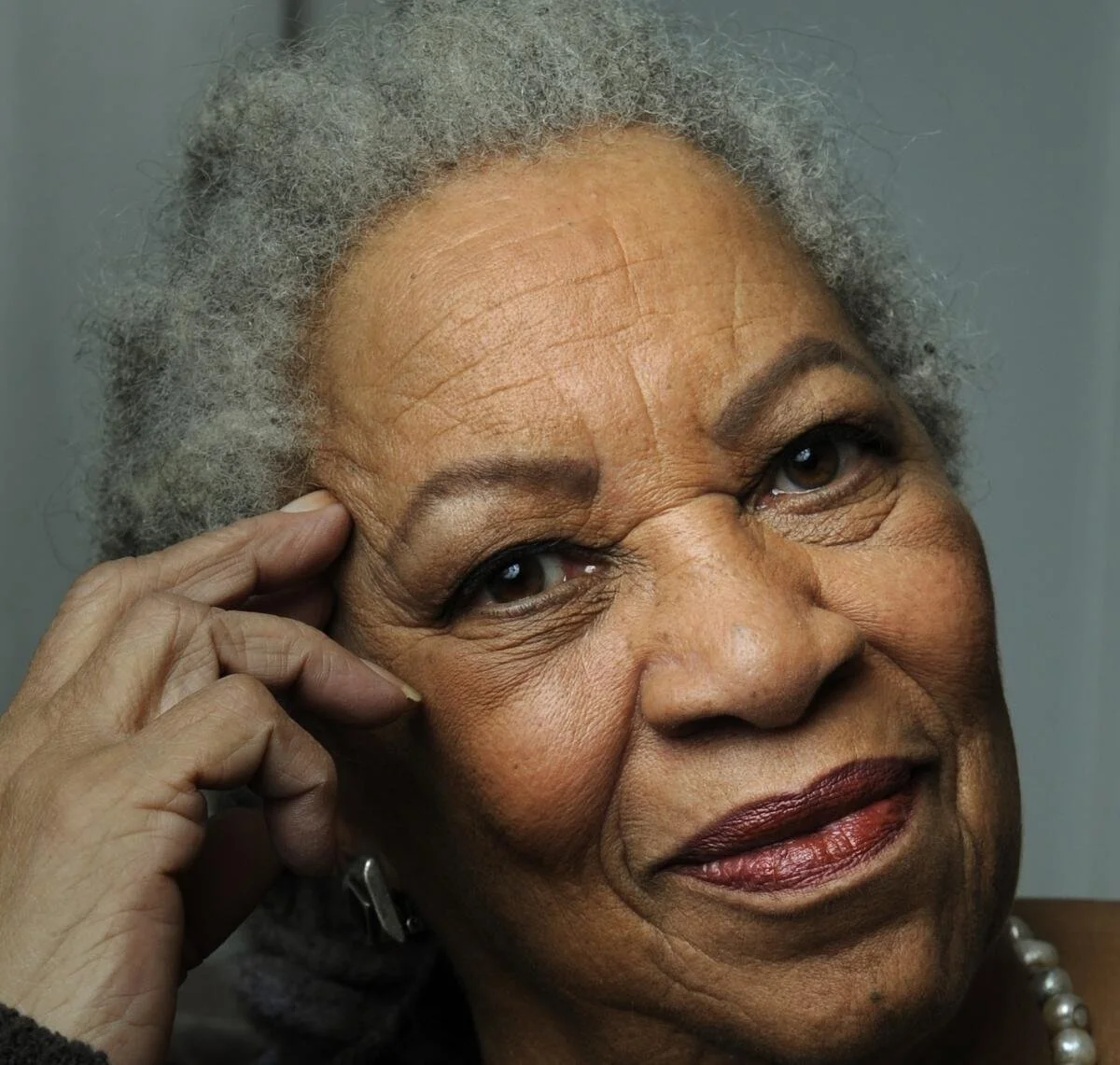

Uppal was adored and in some quarters practically worshipped. Her looks were beautiful, unusual and unmistakable, so that once, when I went to interview the author Barry Callaghan in his home, I immediately recognized a charcoal portrait of Uppal hanging on the wall even though she had been sketched from behind, kneeling, with her head bent so that all I could see was the mass of thick, somewhat African curls cascading down her naked back. But it was definitely Priscila, drawn by Callaghan's artist wife Claire Weissman Wilks. Wilks passed away shortly before Uppal, who died of synovial sarcoma in 2018 at the age of 43. Uppal was not one of my closest friends and yet the ache is dull and persistent. It is hard to say why. I do know that I am not the only person who feels this way. The other day, I saw a facebook post in which writer Natalee Caple burst out, "Priscila, I miss you so much." Recently, I met a woman at a literary function who looked vaguely familiar. She remembered me too, from Uppal's memorial service. Time had passed, yet still, we could not talk about her; the loss remains unbearably fresh. A few years ago, I moved into Uppal's neighbourhood. I am walking distance from her home. Given time, we might have grown closer. She certainly knew how to live: She could have given lessons! When your friends are mostly writers, you sometimes forget to write about them. I am glad I made a point of writing about Priscila Uppal. Whenever I really start to miss her, I can read and remember.

Today I am posting a story about the day I spent in candid conversation with Uppal about her memoir Projection, the story of her attempt to reconcile with her runaway mother.

********

Not long ago I visited Priscila Uppal at her home in west end Toronto to talk to her about her popular memoir Projection: Encounters With My Runaway Mother. When she opened the door we laughed to find we were wearing practically the same dress: knee length bright fuschia jerseys. But mine had a boat neck with a swingy tangerine belt and hers was short-waisted and cut across the bust. I felt pleased as I admire Uppal’s fearless style which lies somewhere between glamorous diva and playing dress-up.

Uppal is the only woman I know who can wear a fascinator as if to the manor born. An invitation to one of her parties called for the ladies to wear hats. I splurged and bought a white one, but when I arrived Uppal was bareheaded. “Where is your hat?” I said, exasperated. “Right here,” she smiled, pointing to the flared skirt of her flamenco gown where the pleats folded like origami into a flat topped chapeau.

Uppal was good enough to give me a tour of her closet which is actually a full dressing room with silver racks thickly hung with shimmery hues of blouses, scarves, belts, pants and dresses and nearly 100 blazers, as many items as you might find in the ladies section of a department store or in a theatre company’s wardrobe. The sign over the door read Drama Queen, befitting her turn as playwright of Six Essential Questions the production based on her memoir. By the window an immense iron tree, with sprawling limbs, held a couple dozen hats. What better metaphor for Uppal who adds memoirist and playwright to the roles of poet, novelist, professor and athlete. Who wears more hats than Priscila Uppal?

Uppal actually invites people to rummage around in her closet, which in a manner of speaking is what she does with Projection, the unsettling chronicle of her reunion with the mother that abandoned her two decades before. “The book is about what happens when two people who have been imagining themselves for years come face to face with the reality,” Uppal explained as we made ourselves comfortable on her living room sofa. “Growing up I think my image of my mother would just continually change depending on what I was going through in my own life,” Uppal said. “Sometimes I had sympathy for her abandoning her family and her responsibilities, and sometimes I would just have disdain for someone who could act this way.”

The prequel to the story is a fairy tale set in Ottawa in the 1970s where a rising, Indian born civil servant and a Brazilian beauty with literary aspirations were happily raising two adorable children. On a Friday 13th domestic bliss crashed to a halt when Uppal’s father, at work in the Caribbean, was involved in a boating accident. Thrown into the water, he swallowed the virus for spinal meningitis and was quadriplegic in 24 hours. Uppal recalled the trauma when I interviewed her in 2007.

“All of a sudden your way of being in the world is completely shifted,” she said. “You have this house that suddenly needs renovations for things like elevators and wheelchair ramps. And medical people are coming around constantly, and Daddy can’t get up, and Mommy is crying all the time.” Six years later, when Uppal was eight, her mother bolted, though not before emptying all accounts, including her children’s piggy banks. She returned once to kidnap Uppal and her brother. But when that effort failed, she disappeared without a trace.

That was before the rise of the internet. In 2002 Uppal was surfing the web for an old review, when an image of her mother, brother and childhood self-flashed onto the screen. “What the f-k is this!” she cried out to her partner Chris Doda who came running. But she already knew: It was the website of her long lost mother, Theresa Catharina de Goes Campos. A list of Theresa’s credits included journalist, professor, creative writer and film critic. A separate page thanked the doctors who were helping her battle cancer.

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (photo by Raphael Nogueira)

Perhaps it was the cancer that impelled Uppal to reach out to her mother. Or perhaps it was the hopeful realization that they seemed to share so much in common. Uppal said she ended up going to Brazil because she was just plain curious. “I wanted to see who the real person was. I had so many mothers in my fiction and in my poetry and in my life. Mothers who were difficult to take, who were absent, dead mothers and in some way all of this was working out my understanding of my own mother/daughter relationship. I think I went to Brazil so I could just stop imagining her.”

Uppal tends not to focus on the limits of the imagination. As an artist, the imagination is her font; as an intellectual it is her ever absorbing topic of inquiry. “I think the imagination is so fundamental to what it means to be a person to what it means to live in time,” she said. “We are always imagining something that is going to happen in the future and reliving something that happened in the past. The imagination has always been my way of understanding the world, navigating the world, understanding people.”

By imagination Uppal means “fantasy-making that is both internal and that can exist as day dreaming but can also have the external product, such as a play or a piece of visual art or what have you.” At York University where she teaches English literature and creative writing her signature text is Don Quixote, a novel “that shows the power of the imagination for both creativity and destruction.”

“Don Quixote is this old man near the end of his life, a bachelor and likely a virgin, who has read so many romances of knighthood and epic quest that he truly believes that that is what he is. He wants to go out and right the wrongs of society. I understand his motivation,” said Uppal. “The world is not as I wish it to be. I am not as I wish to be. Let’s imagine a different reality here.”

In Brazil, Uppal discovers she and her mother share a deep appreciation for the imagination. Both are writers, poets and film aficionados. As a critic, Theresa views as many as eight films a day. Relatives fear she occupies a kind of dream world and even Theresa admits that life on the screen is immensely preferable to the one she has inhabited so far. “Romance should only exist in film,” she tells her daughter, as they exit a screening for Maid in Manhattan. “There would be no pain, no pain anywhere. Don’t you see? Films should be idealistic. Not realistic. Why go to relive misery? Love stories only last on film.”

Theresa, like Don Quixote- like Uppal herself- prefers to imagine a different reality. Rather than drawing mother and daughter closer, however, Theresa’s preoccupation with the imagination pushes them farther apart. She remakes the past, imagining herself the victim of harsh circumstance and physical abuse, and seeing her paralyzed husband and helpless children as having held every advantage. Not surprisingly, Uppal refuses to participate in this scenario.

“My mother is an extreme case of a person so wrapped up in her fantasies that any time I deviated from her script she became upset,” she said. “She really wasn’t willing to accept that I exist as a person separate from her fantasies.”

Anyone might have sympathy for Theresa Catharina de Goes Campos. Her husband’s accident marked the end of a dream. She had not signed up to be the wife of an invalid; she did not possess the requisite emotional resources. As Uppal writes in Projection, “My mother’s misery permeated the household like a nauseating spray.” Theresa’s frustration sometimes gave way to violence. Once she tried to force a catheter down her husband’s throat. She protested her son’s messy room by stuffing a dirty sock into his mouth. Five year old Uppal sought refuge in her mother’s wardrobe. She curled up beneath the clothes, comforted by the caress of fabric against her cheek.

After her mother left, the wardrobe became a favourite place to play. She devised costumes out of dated outfits. She fingered the tubes of Avon lipstick, abandoned just like her. She perused the small pile of rejection slips (her mother had attempted to publish poems) and skimmed through the personalized notepad with the header From The Desk of Theresa Uppal. Working her way through her mother’s belongings helped Uppalwork her way through her anger. At the same time, the objects sustained tactile familiarity: Her mother had touched these things.

Pena Coteca do Estado

Still, when Uppal sees Theresa, plump and effusive in the lounge of Sao Paolo’s stifling airport, she feels no connection: My heart does not recognize her, she says. An awkward intimacy arises as the two spend hours each day roaming the city’s cultural venues. The musical constellation at the Teatro Imprensa, the art show at the Centro Cultural Bosco do Brazil, the sculpture gardens at the Pena Coteca do Estado begin the engaging tour that gives this memoir its sound structure. These scenes envelop us in the imagination of the Brazilian people.Uppal’s powers of description, so lyrical and precise, give Projection the feel of a densely coloured picture book. “The bright lights of the mega city are like neon night flowers opening up to the moon,” she writes of the view from a revolving restaurant. An installation by artist Regina Silveira features two floating orbs that suggest Uppal’s uneasiness: “I observe the spheres approach then repel each other. Contact is elusive and difficult and ambiguous and random.”

The title Projection derives from Theresa’s love of cinema. She has watched her favourite films upwards of 100 times. Uppal’s analyses of a dozen movies, woven seamlessly into the narrative, illuminate the complicated psychology of the mother/daughter bond. Her critique of Ridley Scott’s futuristic Blade Runner, for instance, considers a genetically-engineered human named Rachel who harbours false memories of a mother. Uppal wonders if a person without a mother can really be said to be human. Projection is in large part an exploration of what it means to be motherless:

“Fathers come and go. Mothers are steadfast. No one loves you like your mother. A mother’s love is eternal. Et cetera. Et cetera. It’s why people make a special face of disgust when I am forced to reveal my mother ran off when I was a child,” Uppal writes. “The issue is that look of disgust is usually directed as much at me as at this invisible mother. As with perfectly good furniture left out on the curb, passersby brace themselves for ugly smells or hidden stains or cracks as they open drawers and lift cushions. Otherwise why would anyone throw out a perfectly good chesterfield or vanity?”

These images reveal a repulsion with the self, as if Uppal believes being abandoned by her mother has made her freak. Such are the pathological ramifications of maternal rejection. Although, it is Theresa, not Uppal, who comes across as irreversibly damaged. So devastated is she by the act of abandoning her children, she has all but erased the details from her mind, and so deep is her denial of the past, she cannot bring herself to ask Uppal any questions about the decades she has missed. She does not ask about her daughter’s childhood or school years or friends. She does not inquire into her academic, athletic or artistic achievements.

Theresa is more than defensive about the past; she is defiant: “I did not abandon you. I left your father,” she insists, after the inevitable confrontation. “There is no need to bring up the past. It does nothing. I live only in the present, Priscila. I do not care for the past.” And also, “I don’t have a second for people who don’t like me. If you don’t like me I won’t have a second for you either.”

There is a moment in the book where Theresa seems ready to admit her pain. But it passes, quickly. She remains chilly and unmoved. Consequently, so does her daughter. “It helped that I wasn’t going to Brazil to get a mother’s love,” Uppal said. “That wasn’t the purpose of the trip and I think that terrified my mother, beyond belief. I would probably have accepted a mother’s love had I felt it was something genuine and about me. But that’s not what I encountered.”

Uppal sat across from me on the sofa describing these painful events. She was wearing her massive curls in two thick braids. She looked completely unruffled. On the other hand, moments of her memoir, in sharp contrast, are ablaze with fury. Projection amounts to a blistering maternal portrait. Uppal’s unsparing pen does away with filial obligation. It is by no means cowed by her mother’s on-going illness: Her mother is a “fat” woman who “waddles” when she walks and “shudders” when she cries. Her mother is a woman who stops talking only to shovel food into her opinionated mouth. At night, her mother snores like a “predator.” Her mother’s thick red lipstick- repeatedly described -evokes images of a blood smeared mouth and devoured young. Her mother is a figure of the maternal grotesque.

Projection is not only a cinematic word, it is a psychological term that defines the act of transferring one’s negative emotions to another. With this memoir Uppal deflects feelings of freakishness back to the source from whence they came.

Uppal’s survival skills - honed over long years of self-sufficiency - make her a daunting psychological opponent. Then again, she is not only defending herself, she is defending her father as well. Uppal is the first to admit that Avtar Uppal is a difficult man (she left home at 15; it was easier to attend school and work full time that it was to run her father’s household). Still, she loves and admires him. He is the one who stayed under the most impossible circumstances. “My father is one of the strongest and therefore one of the most difficult men I’ve ever met” Uppal writes. “Sure we have problems- but they are ours.”

Projection gives the impression that father and daughter continue to butt heads. He firmly opposed her desire to study English literature. She enrolled in the program anyway. He hoped a promotion to full professor would limit her writing career. Her literary career continues apace. To this day he rarely reads her work. How does that make her feel?

“Actually my father finds reading difficult, physically difficult,” Uppal said. “He finds it hard to concentrate. But also,” she added, a touch defensive, “I don’t necessarily need my father to participate in my imagination - especially because my imagination for the most part is quite tragic.”

True enough. What parent wants to wander through the minefield of their adult child’s inner life? Uppal perceives her father’s trepidation: “I do think I am scary to my Dad. He probably feels: What’s the point of reading her work? He probably thinks he will feel more alienated from me than he already does. Also my father is South Asian. He is very private minded. He wants to know: Why are you showing your thoughts and fantasies to the rest of the world?!”

Doubtless, Avtar Uppal wishes his daughter had kept her skeletons in the closet. Yet he can hardly complain: He is the one who passed down the gifts of honesty, self-reliance and ferocious determination, the very traits that have proven the secret of Uppal’s success.

Don Quixote’s Great Fight With the Biscayan (by Adolf Schrodter)

Strange as it may seem, Uppal’s mother has also managed to pass down enduring gifts. Some are tangible, material, like the sheer, leopard print blouse, off-the-shoulder turquoise gown and black dress pants with ebony sash she bought her daughter on her visit, all of which Uppal adored. And also, the gift of extended family: The Dresden doll of a grandmother Uppal meets in Brasilia, along with the bevy of relatives brimming with unresolved passions and afflicted pasts; the kind of family that promises an endless flow of haunted stories to be embraced in the manner of Allende or Marquez or Uppal herself.

Finally, it is undoubtedly from her mother that Uppal has inherited the best gift of all: Her imagination - with all its strangeness and beauty, power and limitations.

Projections: Encounters With My Runaway Mother was nominated for a Hilary Weston Writers' Trust Prize for Non-Fiction and a Governor General's Award.